Bad Grass with Mike Nadeau (transcript)

The below is a transcription of the conversation that took place on February 9, 2023 at the White Hart Inn

Jeb Breece:

Thank you all for coming. I’m Jeb Breece, one of the people behind Bad Grass 2023. I’m joined by Mike Nadeau. Mike’s bio is in the program so I am not going to spend a lot of time introducing him. What I will say is that after spending over 40 years making meadows, there are very few people who know more about this than Mike. In my day job, I spend most of my time thinking about businesses and when a business has an edge, a competitive advantage, they don’t share it. Mike is the opposite, he is willing to share everything he knows with anyone who will listen so that other people can turn a little bit of their bad grass into something better.

But, Before we get into that, I want to talk a little bit about why we are here. Why this speaker series exists. There are really two reasons.

The first reason goes back to last summer when Amy Cox Hall, one of my co-conspirators in this project, and I were sitting on the front porch of the White Hart. I was saying how happy was that my family was living here full time. Amy gazed into her cup of coffee and said, you know, there’s not a lot going on in the winter. It gets pretty lonely. I’m not sure this is what she had in mind, but here we are. Amy you were right, people are looking for something to do. We sold out a show about growing grass.

The other reason is more personal. I’ve spent a lot of my life living in a house surrounded by green lawns. And never once, not even when I was a young kid unhappily pushing a lawn mower, did I think what is the deal with this lawn. Why is it here.

But when my family and I moved to Salisbury my other co-conspirator, Page Dickey, convinced me to take a deeper look and see what the deal is with all of this grass. And once I saw, I couldn’t unsee. The green lawn that I’d always thought of as natural and sustaining of life, was anything but. Kentucky blue grass isn’t even from Kentucky, its from North Asia and in its short-clipped state, supports almost no life. What’s more, I realized I was actively perpetuating this unnatural state of affairs by mowing weekly, fertilizing, aerating, watering. I need to do something differently.

In their own way, everyone participating in this speaker series has come to the same conclusion. Mike has spent over 40 years making meadows, but he didn’t start out that way. He actually started in a a very traditional mow, blow, snow landscape business. Only after observing that he had to use more and more and newer pesticides to keep weeds and insects at bay, did he begin to try to work with nature rather than fight it. After seeing the impact on the birds, bees and butterflies, Deb and Page have chosen to avoid invasives and weave native plants into their garden designs without sacrificing aesthetics, Toshi left his job to as director of horticulture at Wethersfield to work with public gardens to build less chemically dependent landscapes. You could say that Star is the exception since sustainable forestry is literally in his blood, but even he will discuss how his practices have changed over time.

Believe it or not, the purpose of this speaker series, for all of us who put it together, is not to tell you what to do with your yard. You’ll do what’s right for you. It’s really to illustrate that we are all making choices everyday with our gardens and to show you some alternatives to the status quo.

And, with that, show of hands, how many of you have lawn at home?

Audience:

Laughter

Jeb Breece:

There’s, there’s, no shame. That one’s mine, that’s mine. I’ve got plenty.

And, so, that’s what really Mike and I want to talk about. Because probably like me, most of you have this lawn and you never really stopped to think. What is it? Why? So Mike, we’ll start with the first one. What actually is a lawn?

Mike Nadeau:

Okay, hello everybody. First, I want to say, wow, this is fabulous. Great turnout and I know some faces so thank you for coming.

So, what is a lawn? A lawn is something that covers the ground. Something that holds the soil in place. What happens in America is that we’ve found lawn to be very aesthetically pleasing and desirable. So we’ve covered a lot, even most of our properties with lawn. And our lawns are comprised of specialized mix of seeds of species that don’t grow here naturally. And some of them might be even invasive. Most turf grass species that are used today are not invasive, but they're not native at all, and they have very, very little ecological value besides eye candy for us. So, that's basically what a lawn is.

Jeb Breece:

And despite having no ecological value, we're putting a lot into them.

Mike Nadeau:

Oh, yes. Imagine this. So, we water them and fertilize them so we can cut them more. And then, we blow all the leaves off, which is exactly what the soil wants, in moderation, of course. But think of all the embodied energy that goes into your lawnmower. A friend of mine, Bill Ducey, who's passed away about 40 years ago, did a study of a lawnmower from iron ore all the way to the finished project, and the embodied energy that was involved in that. The trucking, the mining, destruction of land, and then the gas, the gasoline, and the labor that goes into the care of a lawn.

Okay. So, the embodied energy that goes into a lawn is really tremendous. It's one of the highest maintenance inputs that you can have on your property. I call it the spoiled brat of the plant kingdom. If you have a lawn that's used to be mowed at two inches or even three, fertilized often, pesticided, what you have really is what we call rugs on drugs. So, you take away those inputs and the lawn will die, or at least crash. So, it is a real sink on our environment. So, just the watering alone, I've got some facts that I'll read to you later.

Jeb Breece:

You can read them now. We can give them the facts.

Mike Nadeau:

Okay. So, I'm not going to bore you too much with these, but does anybody have an idea...this is kind of a dead giveaway, but what is the largest irrigated crop in the United States?

Audience:

It's grass.

Grass.

Mike Nadeau:

It is lawn. Can you imagine? It is not corn. It is not soybeans. It is lawn. 40 to 50 million acres of lawn right now. 9 billion gallons of water per day. Lawns are a soul-crushing time suck, The Washington Post. Love that one. What's more polluting... Get this one. What's more polluting? And there goes the technology. What's more polluting, a 411-horsepower, 6,200-pound Ford Raptor pickup, or a leaf blower?

Audience:

Leaf blower.

Mike Nadeau:

Which one? It's amazing. A two-cycle backpack leaf blower generated 23 times the carbon monoxide and 300 times more non-methane hydrocarbons than the Ford Raptor did. And that's from the AAA Automobile Research Center. 18 million pounds of pesticides, 18 million pounds of pesticides are used on American lawns yearly, from the Pesticide Action Network. That's just lawns, let alone the soybeans and the corn. No biodiversity, no pollinators. Lawns are an ecological desert, the National Science Foundation.

Jeb Breece:

So, given all that, why do we have lawns? You touched on some of the aesthetic, but where did it come from? Is it all European aristocracy?

Mike Nadeau:

So, Europeans cut down most of the trees for various reasons. One of them was for farming. So, ruminants like sheep forged on the resulting vegetation, keeping it low and uniform. The more grazing animals, the wealthier the landowner. These grazed lawns, in quotation, became a status symbol of the rich and the powerful in England. And Thomas Jefferson, when he came here and founded America with a bunch of other patriots, in 1806 was the first American to replicate the European lawn at his Monticello estate. So, he brought that aesthetic here. And he used not grazing animals, because there’s was a bowling green where they played on the lawn, so they wouldn't want ruminants pooping all over the place, so he used slaves. So, the lawns were maintained with slaves.

So, that's where it came from. And then where it developed in the United States. So, there's something different from a lawn and a monoculture lawn. So, when I was growing up, anything that survived under the mower blade was your lawn. So, we had dandelions, we had plantain, we had some crab grass, we had some violets, and we had some grass. And it was resilient. It was great. And I never knew that it was wrong or bad until I went to school and I got filled with the Dow mantra that many of us may remember, better living through chemicals. Remember that one? Yeah.

So, anyway, during World War II, the federal government paid the newly-emerging chemical industry to create a material that would defoliate a jungle so the enemy would be exposed. The war ended before these chemicals could be used, so the chemical companies put together think tanks to find ways to use this new technology called herbicides. Some of the chemicals killed only the broadleaf plants and didn't kill grasses, so they made the dandelion public enemy number one. Does anybody remember... I think it was probably the 60s, when they had the picture of the dandelion? This was on TV, the black and white. And they showed the dandelion turning into a lion, and it was going to eat your kids. So, the last thing you wanted in your lawn was this lion. And it was this great big yellow thing with teeth. I remember what it looked like.

Before herbicides, lawn consisted of the matrix of plants growing in harmony with each other, including dandelions. The selective herbicides were marketed to us as a way to have the Earth-Tech lawn, grasses only and nothing but grasses. And that's how the weed-free American lawn was born. And here's one of my hopes. I hope to live long enough when the people who grow monoculture lawns will be thought of in the same way as we think of smokers on an airplanes. That is all.

Jeb Breece:

So, thanks for the short history lesson. We could go on and on about the sort of narrative around grass and lawns, man versus nature, status symbol, HOAs. It's a way to show that we're all together as one and adhere to the same value system. But that's actually not why we're here. We're here to talk about getting rid of laws. And I touched on it, in the beginning you didn't start out making meadows. You evolved into making meadows. And so, tell us a little bit about how that evolution took place for you.

Mike Nadeau:

Okay. So, I guess you'd call me a nature boy. So, back in the day, my heritage is from Maine. So, I would go to Maine often and I would spend a lot of time with my Uncle Shiner, who was half Native American. And he had this beautiful spirit about him. I mean, he did things... I'll give you one little quick story. I was walking through the woods with him one time. It was in the spring. And he was a forester. He owned 2,000 acres of land that he selectively harvested one tree at a time, and just loved his land and loved his trees and made his living from that. And I was running ahead of him, and I saw something off trail. I forget what it was. It might have been a flower or whatever. And I went to run off trail, and he very gentle grabbed my shoulder and kept me on the trail, and knelt down in front of me, and said, "We don't walk off the trail in the springtime because the earth is pregnant." It blew me away.

So, I decided I was going to become a nature boy, and I did. And along with that came the conventional learning. I learned a lot about how to kill and control nature, and I'm not proud of that, but that's what they taught us. And I drank the Kool-Aid. And then as time went on, I noticed, as Jeb said, that I had to use more and more stronger pesticides. Synthetic fertilizers were coming out, and I was using all of that.

And I noticed several things. One is, I wasn't feeling all that great physically, and I started to have holes in my beard. I grow a beard every winter, and I shave it off in March. So, I would have these diamond-shaped bare spots in my face where hair wouldn't grow. And I went to the doc and I asked him, he goes, "Hmm, that's funny, because facial hair is connected to something called cholinesterase in your blood." I never knew this. So, he did this cholinesterase test and found that my cholinesterase was off the charts, way off. And he asked me, he goes, "Are you around organophosphate chemicals?" I said, "Of course I am. I drink them, almost."

So, that was one thing. The other thing is I saw diminished ecological health. I saw fewer birds. I saw fewer insects, beneficial insects, which by the way, we never learned that term in college. Beneficial organism was nothing we were ever taught. Every organism had to be killed or controlled. So, I noticed that trees especially started to die from the tops down where that lawn, perfect lawn, I was growing underneath with the pesticides and everything. So, I became aware that I was doing something wrong, but I had no idea how to change it. So, that's my evolution from there.

Jeb Breece:

And early on, I'm sure there were not a lot of people doing this. Earlier this year... Mike and I have worked together on a meadow at my house, as well as Salisbury Land Trust, where we've worked together on their meadow project And I was shocked that Matt, who's the contractor we're working with, he's working on 11 meadows with you in the northwest corner of Connecticut.

Mike Nadeau:

Just this year.

Jeb Breece:

So, is that an increase in demand? Is this a movement that's taking hold?

Mike Nadeau:

Yes. Yes. So, people are realizing... How many people have read the New York Times Magazine article, Insect Armageddon? Okay. And then, you have told two people, and then they have told two people. So, there's serious evidence in proof that we are in really bad shape as far as insects go. And if the insects go, so do the birds. And if enough insects go, so do we, because 85% of the plants we eat are pollinated by insects, and we need them to do that in order to grow food. So, what was the question?

Jeb Breece:

Well, I was actually leading you to talk about Matt and how he's evolving his business.

Mike Nadeau:

Oh, yeah. So, anyway, the phone has been ringing quite a bit. There's people that are really aware that we have too much lawn, and also the whole native move, the native plant movement has gained a lot of momentum. Back when I was first using natives, I couldn't tell my clients that they were using them, because they were gross or coarse. Everybody thought they were less than the hybrids or what we could get from Europe or Asia. And now it's really involved.

A lot more people are getting educated that what we've been doing is really wrong and we're headed in the wrong direction fast. Einstein said this great quote, "We cannot solve problems with the same thinking that created them." So, the whole idea around trying to think our way out of this problem by using the same thinking is really problematic.

So, the whole idea now is to have enough lawn, what you need... It's not bad. It's not a bad thing. But care for it properly. In other words, reduce your pesticides or actually eliminate them. No synthetic fertilizers, right size, and the rest of it, do something ecological. There's no need to have all that lawn. If you have kids and they want to play it, throw a football around or whatever, have lawn. But when the kids grow up, which won't be long, as soon as they find out about all this, by the way, they won't be out on the lawn much. So, you have a plan already that you then transition your lawn or whatever you have to something more ecological.

And Matt happens to be in the audience here somewhere. There he is. All right. So, Matt owns Matt's Landscaping, and he has found me and I have found him. And one of the biggest problems with this movement is there are very few genuine practitioners. People think that if you just scatter some wildflower seed on the ground, it's going to just turn into this magic meadow. Well, this is definitely by far the most complicated landscape I've ever done, a wildflower meadow. It is so incredibly intrinsically smart. It's got so many nuances to it.

So, it needs special training, and Matt has really stepped up with me. And what I'm doing is I'm doing a mind dump. Who's a Star Trek person? I'm doing a Vulcan mine-meld with Matt. And Matt is way ahead of me. He's already trying different things and experimenting, and he's got the equipment and the crew. And this is not shameless commerce. This is what I'm telling you the biggest problem is, is we don't have enough genuine practitioners. So, I'm trying to teach as many people as I can. So, that's why I'm here.

Jeb Breece:

So, I've been waiting for this pun all week. Should we get into the weeds of...

Mike Nadeau:

Let's get into the weeds.

Jeb Breece:

Okay. So, as I said, this is...or was my lawn. And we're going to take you through all of the steps up until now.

Right now anybody who drives down Main Street sees it as maybe not the meadow they envision when they think of a wildflower meadow. It's looking a little flat and dust bowl-ish. But we're on our way. So, this is where we started. And as someone wanting a meadow, wanting to get rid of lawn, I'm immediately, the first time I talked with Mike, wanting to think about the finished product. And Mike was pushing me back to the first step, which is a clean slate. And so, really, the next few slides are about getting that clean slate, and I'll let Mike talk about what they are.

Mike Nadeau:

So, that's Matt's crew there. So, what's most important with wildflower meadow from seed especially is 100%, or as close as you can get to 100%, vegetation control before you sow seed. If you fail with site preparation, your meadow will fail. 40 plus years of experience, I've never found a shortcut around this part. So, if you have lawn, that's a piece of cake to control. I hate using the word kill.

So, to be able to eradicate the lawn is really the simplest plant I know of to eradicate. When you get into the basic weeds like mugwort and woody invasives, the work is a harder. It takes a lot more inputs. I tend to do all my work organically, so I'm not really involved very often with synthetic pesticides. However, we do use them. They're a tool. Synthetic pesticides are a tool, just like the organic herbicide that I use is a tool. But it's to be used as a last resort and extremely sparingly. So, there are plants... mugwort. It's really a thug.

Jeb Breece:

So, right here, this is my layman description of what going on. You are vacuuming the yard.

Mike Nadeau:

Mowing, scalp mowing, and then vacuuming all of the debris out so that we would have nothing in the way of the next machine that we used on the property.

Mike Nadeau:

So, that's vacuuming, mowing, and then this is a machine called a Harley rake. And this machine is being driven backward, and this roller in the front is pushing all the material forward. So, what we're doing is we're shallow tilling the root system of the lawn after it's been mowed and vacuumed. So, all the mowing and vacuuming takes all the detritus off and leaves just this little stubble and then soil. So, this is how to do this organically.

Jeb Breece:

And this is where we ended up. This is what it looked like.

Mike Nadeau:

So, that's exposed roots, most of it, that we allowed to sun dry.

Jeb Breece:

So, then the next step here is...

Mike Nadeau:

The vinegar application.

Jeb Breece:

... the vinegar application. And it's not just vinegar. We're not spraying balsamic, correct?

Mike Nadeau:

No, we're not spraying balsamic. We're spraying something that's very, very dangerous to you. So, I want to add that right up front, is that just because it's organic doesn't mean it's safe. It's safe in the right hands. Matt and I use it all the time, and we're careful, we're cautious, we know what we're doing. So, anybody that uses this must too. I want to explain one thing. What you see is the regrowth after the Harley raking. So, that is what sprouts back up.

Jeb Breece:

And that was about two to three weeks after.

Mike Nadeau:

About two, three weeks after. And the lawn does not want to die. You're not going to go through, till you lawn once, and then have it just give up. So, you need to do this several times. So, what we did was we used vinegar mix, and it's 30% agricultural vinegar with citrus soil, 100% pure citrus soil, and salt flour, which you buy from a restaurant supply store. So, it's salt that's pulverized out to a flower, gets mixed into the vinegar. And then, dishwashing liquid, believe it or not, just regular, good dishwashing liquid, because that acts as a surfactant and allows the vinegar to spray evenly over the weed. And then last, we use a blue dye, so we know where we sprayed, where we didn't, and how dense we sprayed or how lightly we might have sprayed by the color of the blue.

Jeb Breece:

And this is what it... It looks bluer on our screen, but this is what it looked like when it was done. Probably many of you remember seeing this on the land trust property or on ours as you drove down Main Street. I think my wife would attest, we got more questions about what we were up to when it was painted blue than any other time in the process.

Mike Nadeau:

One thing you can't see here is the smell. 30% vinegar reeks, and it stays like that for a little while, probably, depending on the weather, but probably two, three days. It's pretty strong.

Jeb Breece:

So, then after two or three sprays, in our case, I think it ended up being three, although two was the plan, three coats of the vinegar and we were ready to seed.

Mike Nadeau:

Yes. One other thing I want to state is that if anybody's going to use vinegar, make sure that you really read the label and get your personal protection equipment. Hire someone who knows what they're doing with it. And here's the biggest thing to know. The acetic acid in vinegar is extremely volatile so that it will turn into a gas and blow off, and when it blows off, it might blow into your prized rhododendron, and it will kill it. So, the whole idea about using vinegar is very coarse, thick spray. No drift. So, low pressure, high volume, so you're soaking the plants, you're not spraying the plants. Really important.

Audience:

Does it impact the trees that you have?

Mike Nadeau:

Not the root systems, no, but if it volatilizes, it will. Yeah.

Jeb Breece:

And so, you can sort of get an idea of what it looked like after three coats of vinegar. There was really not much left.

Mike Nadeau:

It was pretty dead.

Jeb Breece:

Pretty dead.

Jeb Breece:

And so, the seeding, and this is not just, as Mike said, just throwing seeds around. This is actually a precision instrument.

Mike Nadeau:

Yes. So, this is Matt's TRUAX no-till seed drill machine in the back of that tractor. So, basically what it does is it cuts little slits and then has three different boxes for different size and different fluffiness of seeds. The seeds then blow down through these little tubes go into those slits, and then there's rollers after that that cover the slits up. And I've never had such good germination as using this machine. Hand scattering the seed is something I do with many smaller meadows or where you can't get a tractor in. And incorporating the seed afterward is really good. But this, I found, has an incredible germination rate.

Mike Nadeau:

So, if you look at those rows, see those slits, and look at the vegetation. All those little babies, those are all wildflowers. And we went in two directions. If you back up, back one... I'm sorry, two. So, you see we're going in two directions. We're going 45 degrees to the first application. And the reason why is we didn't want to run out of seed, plus we wanted to make sure that it didn't look like cornrows when it germinated. But the most important thing was not to run out of seed. We used cat litter to bulk up the material and then there's lots and lots of testing, measuring and weighing, to make sure that the machine is calibrated properly.

Mike Nadeau:

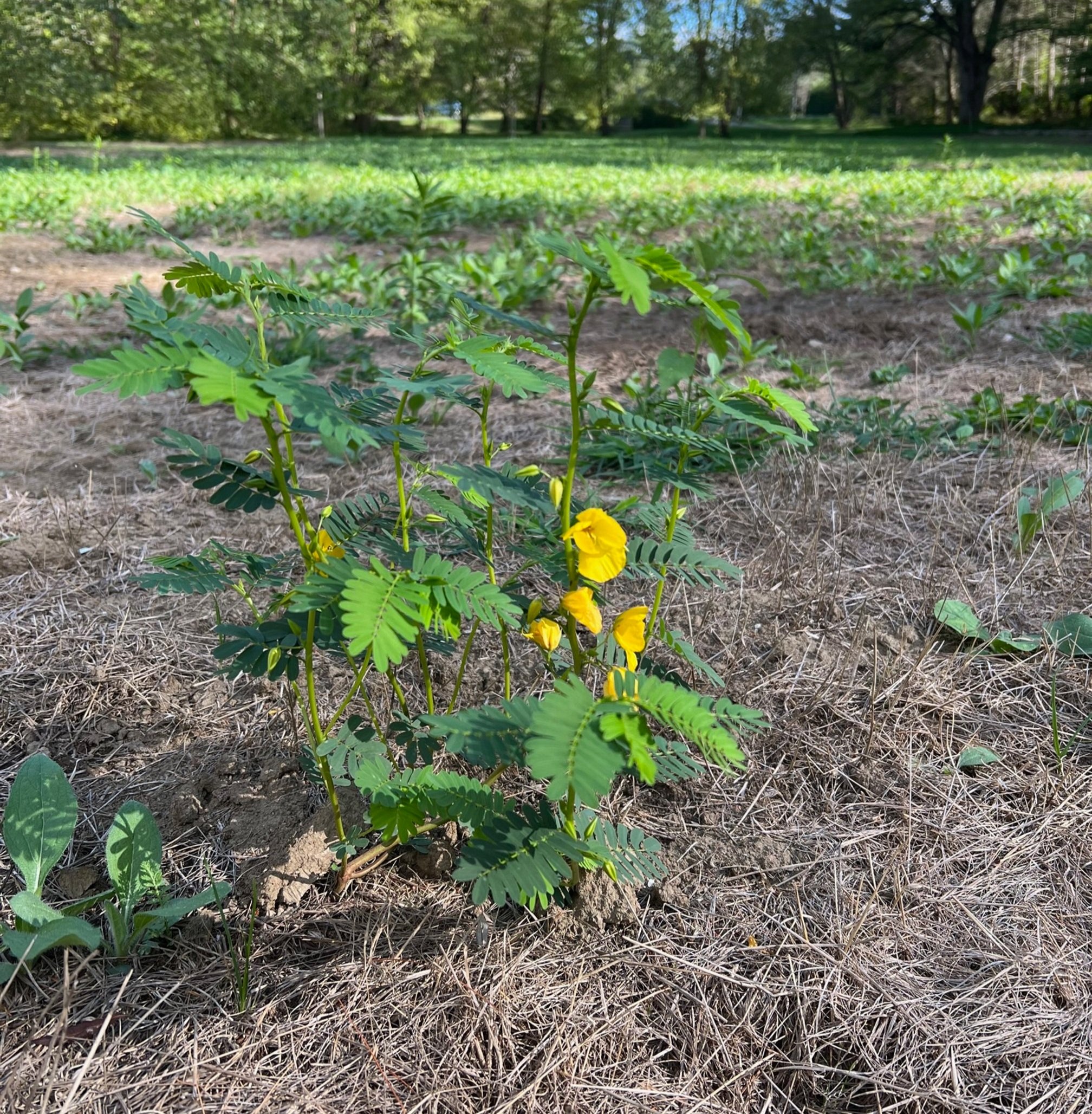

And those are our babies. So, those are all wildflower flowers to be. However, not all of them. This one is one plant we're going to be talking about soon. Chamaecrista fasciculata. What's the common name?

Jeb Breece:

Partridge pea.

Mike Nadeau:

And that's a weed. So, as well as we did with the vinegar, we still have some weeds. So, there is some work that needs to be done. It's usually a three-to-five-year maturation time for a wildflower meadow. And after that five years, it's constant vigilance. You can never let it go. Just like your lawn, you can't let it go because the invasive pressure is weed seeds coming in. Every time somebody comes onto your driveway with a car, could be bringing weed seeds in. Every time it rains. Birds drop seeds all the time, and they'll germinate just beautifully in this meadow until the meadow becomes really, really thick. And the thicker it becomes, the more diversity and complexity in the meadow, the less weed germination you will have.

Jeb Breece:

So, in Mike's view, getting the clean slate is the most important part, it s the highest degree of difficulty. But I think he actually undersells the seed mix and the degree of difficulty there, because as he explains, and we're not going to go through every one, but as he explains how he's put together this mix, he's thinking on so many axes. If it's longitudinal time with plants that bloom early and then fade away, thinking across seasons, thinking grasses versus flowers, thinking height, thinking not just height above ground, but root structure below ground. Filling all the voids.

And so, this is the seed list, which we're happy to share. This is for the Salisbury Land Trust Meadow that's on Main Street. But we actually picked a couple of plants that you're going to talk about to give a little bit more about the plant itself, but also where it fits in that succession on these various axes.

Mike Nadeau:

So, I should probably talk a little bit about the mix. So, this is Salisbury Land Trust mix, and it was more of a utilitarian wildflower meadow. So, I didn't go with real high diversity. I went with a lot of tough thuggy plants knowing that they're going to take a foothold quickly and establish and be really tough. So, one of the things about wildflower meadows is the seed that you buy, if you buy a mixed wildflower seed mix that's been already mixed, how do you know about your soil pH? How do you know about how wet or dry your soil is, how rocky or clay-y or compacted the soil is, how much sun and shade you have?

What I found is that some wildflower meadow seed mixes are consisting of quite a few plants that are in abundance at the seed house. So, they have extra. So, those go into the seed mix. Also, old seeds that are close to the end of their germination period might go into the seed mix. So, a fresh seed mix separates the men from the boys. I know that sounds sexist, but it really makes the difference between a meadow-scaper and someone that can throw wildflower seed down on the ground.

So, the nuances here is, like Jeb has alluded to, there's a time scale that we're working on, and not only in years, but in early, mid, and late succession of these plants. So, this mix has been chosen for early, mid, and late successional plants. So, this meadow will evolve over time. The first couple of years, you get a lot of black-eyed Susans, daisies, things like that. Some of the wild rye grasses will come up and look really beautiful. And people fall in love with it right there. But guess what? Don't fall in love, because it's going to change, and it's going to change, and it's going to change, and it's going to mature.

And sometimes, it takes years for the grasses to come in. The grasses are very important, which we'll talk about later. But the nuances for a seed meadow mix is you want to make sure that you pick fair fights. You don't want to put me in the ring with, say, Muhammad Ali. Okay? What you want are plants that are compatible, that grow together for ecological reasons. So, if you think about it, think about root systems. How often do we think about the root system of the plant? So, some, like grasses, grow really, really deeply, and they can go into the B and C horizon and take minerals up from way, way down below. Others are in the middle. They'll go maybe a foot, foot and a half down, depending on the soil conditions. And others are really shallow. And then there's all of those that are in between.

So, if you put all deeply-rooted plants together, guess what? They're all after the same minerals and nutrients and moisture. There's too much competition. It's like a forest with too many trees. If you can figure out their root systems and choose the plants accordingly... Also, their growth habits above ground. What is going to be my ground cover? What are going to be the plants that grow up and then spread out? What are the ones that grow way up like a vase and then open up, that allow all of the other ones to grow? And then, what about the textures and the layers? So, so important are these layers. If you do not have the right layers, you'll have weeds. So, that's why three to five years down the road, if it's properly chosen, properly cared for, properly prepared, you should have a fairly self-sustaining meadow.

Jeb Breece:

Yes. Do you want to talk about this...

Mike Nadeau:

Sure. Okay. So, we're going to pick three plants out of the myriad of plants that we could use in wildflowers. I chose this one because swamp milkweed gets a bad name because it has the word swamp in front of it, especially since number 45 told us all to drain it. And wherever swamps are, they are earth's filters. They're so important. And that's why there's wetland commissions in every town that protect and tell us that the swamps are really important. There are certain plants that grow there, and one would be this Asclepias incarnata, or swamp milkweed.

It's a favorite of monarch butterflies. As is common milkweed, which is its sister, Asclepias syriaca. Both of them are really good butterfly attractors. They're a great nectar source for butterflies, especially monarchs, and also for hummingbirds. They have a bladder-like seed pod. We all pretty much know what they look like. They split open, and each seed is attached to a silken parachute to help the seed be dispersed by wind. And they're beautiful to watch come out of the pod during a windy day.

Stems and leaves exude a toxic milky sap that monarch caterpillars are immune to. So, they're poisonous to birds. So, what a cool thing nature has done, huh? It creates this poison that the butterfly larvae love. They eat it, they become poisoned themselves so that they don't get eaten. It's pretty cool. What a nice trick. And it's deer resistant. It's one of the wildflower plants that are deer resistant.

The other one is partridge pea, which I pointed out before.

Jeb Breece:

Well, just before we move on, in the succession of your meadows... I know from experience, this germinated quickly, came up in the first year. Is it a long-lived plant in the meadow?

Mike Nadeau:

No, it's not a long-lived plant. It is an aggressive plant. If it has a lot of room, it will spread and become monocultural in some conditions. But what I found with swamp milkweed is it'll find its place and it'll always be there, but it will not be in the proliferation in the early stages of the meadow.

Jeb Breece:

All right, so onto partridge pea.

Mike Nadeau:

Okay. Partridge pea. And I love the Latin name of this one. I know it sounds like I'm showing off, but if you go to China and you ask for a Chamaecrista fasciculata, you're going to get this plant. If you ask for partridge pea, they're going to look at you like you have three heads. So, there's a reason for this, by nomenclature. So, anyway, partridge pea is a native annual, very unusual. So, it's native to this area and it's an annual, and it makes a really good meadow plant because it's an early colonizer and a good plant for weed control. Doesn't look much like it there, but that will spread into a little bit of a small shrub-like plant. And then, it will sprawl over the ground. And in the first probably three years of the meadow, it actually gives me some weed control.

It's also a nitrogen fixer. So, 67% of what we're breathing right now is nitrogen. This plant can absorb it through its leaves. And then, in partnership with a rhizobium bacteria, very, very specific bacteria, in the soil, it creates these nitrogen-fixing nodules on its roots. The nitrogen in those nodules is plant-available food. So, it's feeding the meadow a little at a time. Oftentimes, we don't use legumes in the meadow because we don't want to richen the soil, but this is one I always use.

It's a beautiful plant. It has pinnate compound leaves that are like a fern, and it's sensitive to the touch and to sunlight. So, if you touch those leaves, it'll close up on you, and then it'll open up a couple of minutes later. And then when the sun goes down at night, they close up, and then they open up again. So, it's really interesting to show kids this plant. It has a yellow pea-like, pea type flower. They're like little miniature irises if you will. And it blooms from summer to frost. It is host plant to the gray hairstreak and the cloudless sulfur butterflies love this plant.

And this is the coolest thing about this plant, I think. Not only that it's a native annual, but it's only pollinated by long-tongued native bees. So, our honeybees, that is not native to the United States at all, cannot pollinate this plant because it doesn't have a long enough tongue. So, these native pollinators, these native insects are so, so important.

Jeb Breece:

And just to point out, this picture was taken four weeks after we seeded, five weeks after we seeded. So...

Mike Nadeau:

It's an annual. It wants to do its thing right away.

Jeb Breece:

Yeah.

Mike Nadeau:

And then I included the grass. So, grasses get short, shrift in meadows, I try to keep at least 40% grasses in my seed mixes. The reason why is because they're a heck of a lot more sustainable and easy to grow than forbs. Also, they fill an ecological niche, which is really important. One thing to know about this grass... So, this is switchgrass, or Panicum virgatum. There are many, many different ecotypes of Panicum virgatum. So, if you buy a Midwest ecotype, so if you buy your seed in a seed mix that comes from the Midwest, you might get a seven to eight foot tall plant that is going to spread so much seed that this plant is going to become a real nightmare in your meadow.

However, there are ecotypes that are close to here. One is the Albany pine barrens ecotype, and the other one is the Long Island coastal lowland ecotype. They're much shorter and they're less aggressive spreaders, much less aggressive spreaders. So, that's important to note. To use this plant, you have to be... It's a little tricky. I keep it pretty low on my percentage in my seed mixes because I don't want it to take off.

And, It attracts birds. So, it brings birds into your meadow. And the reason why is they can sit on top of those leaves and blow in the wind and be perched and look for what they want to do next. Who knows what birds are doing when they're just sitting? But they sit on these plants quite often. Think about nesting material, think about seeds for food, think about cover. When something like a hawk comes by, they can dive inside that vegetation and be invisible. They're really deep-rooted and long-lived. They have a really strong upright habit, so other plants can lean against them.

So, I want to say one cool thing about New England aster, Aster novae-angliae. If you planted it in a garden like the straight species of many hybrids now, but if you plant the straight species in a garden, it will flop if you give it plenty of room. It'll look beautiful, but it'll flop over. In a wildflower meadow, if you walk through a native wildflower meadow, you will see the asters are three feet tall. And the reason why is because they're leaning against their brothers and sisters. This has a lot more lignin in the stems, so it gives them a lot more stiffness and strength that the New England aster doesn't. So, they lean up against each other. They pick fair fights.

So, a plant that's three feet tall can have a lot more leaves, especially in that kind of competition in a meadow. Leaves are important because they're the solar panel of the plant. What else do I have here? It's deer resistant, and also, native grass with pinkish seed panels in the fall, and some of the fall colors can be purple, oranges, rusts, and fawn colors. So, it's a really important plant for me, not only aesthetically, but it fills a niche. And one thing I want to say about meadows is if you don't take up all the niches with below-ground and above-ground vegetation, nature will fill it with something, and it generally will not be something we want. So, take up all those niches with desirable vegetation.

Jeb Breece:

So, for a finished product, it was very tempting to show a beautiful landscape with a big perspective. But actually, Mike and I wanted to zoom in, because we started off talking about a monoculture lawn, and I think this is the best illustration you can get of how a meadow is the opposite of a monoculture. There's so much going on here, which I'll let Mike tell you what it is.

Mike Nadeau:

So, lots of diversity here. I won't go through the plants and all that, but you probably know brown-eyed Susan and mountain mint. But what I want you to see is what you don't see. Do you see any soil here? Do you see any mulch?

Audience:

No.

Mike Nadeau:

No. That's the key. That's the diversity, that's the layers, that's the weed-inhibiting growth of a well-planned-out meadow. It's got all of these layers, and all of these things help each other. So, the diversity in here is... there's enough pollinator food for any insect that wants to come in, and there's room enough underneath for all kinds of other things to live and lay their eggs there, and they hatch out, and then the birds come underneath those.

So, I don't know if anybody else has noticed this, but in my yard, we saw one bird this morning. One bird in my yard, and I live in the woods. It's with a little bit of a lawn and lots of native plantings all around. We saw one bird. And the bird count is here. I don't know if you noticed the Audubon bird count was extremely low this year. And one of the reasons is because there's no insects. And the reason why there's no insects is because there's too much damn lawn. We're spraying way too many pesticides. We growing monoculture lawn that cannot be used by the insects or by the birds.

So, what we're trying to do here is, lawn is not a bad thing. Excessive lawn and synthetic lawns are bad things. Bad grass. We're not talking about what we used to buy in plastic bags in high school.

Jeb Breece:

So, that's where we'll open it up for a Q&A. The last slide that we put on here was actually... We thought it was seasonally appropriate, and a pitch for meadows all year round, because this to me is a lot more interesting than a brown, gray expanse with grass this time of year. This is actually a friend of many of ours meadow in Sharon,, which is spectacular.

I think that we've got a small enough room, and that if everybody speaks up, we don't need to pass the mic around for a Q&A. So, we may repeat your question just so everybody can hear it, but if anybody... Maybe we covered everything, but...

Audience 1:

Do you use any seed that are parasitic to grass? I heard that yellow rattle is really good for preventing the grass from disturbing the meadow.

Mike Nadeau:

You're hired. I have never heard that. That's great.

Audience 1:

It is common in the UK. I don’t know if it is a thing here, but that's something. It's called yellow rattle.

Mike Nadeau:

Yellow rattle.

Audience 1:

It's a flower and it prevents the grass from spreading.

Mike Nadeau:

Wow.

Audience 1:

So then, the full wildflowers won't have-

Mike Nadeau:

Matt, make a note of that.

Audience:

Can you repeat the question?

Mike Nadeau:

Okay. The question is, have I ever tried this thing called yellow rattle that inhibits grass from growing back? And I have never even heard of it. You?

Audience 2:

They use that over in England a lot. It's known as yellow hay rattle, and it's parasitic to the grasses, and what it does, it slows the bigger grass down to allow the other flowers to take over, the other plants. I've looked into it here, because I used to see it all the time with the native grasses in the UK, and there is a native one here, but apparently a lot of people don't like to use it because the farmers get upset with their hay, because it slows their grass down.

Mike Nadeau:

How about our native grasses that would be in the seed mix? Does it inhibit that too?

Audience 2:

I wasn't sure. We have a lot of native bluestem, and I was sort of concerned that it might be an issue with that. So, I haven't tried it yet. I'm going to do that in a small pocket and see how it reacts, but I haven't used it at all yet.

Mike Nadeau:

That's wonderful. Thank you.

Audience:

Hi. Could you tell me, is there a mowing cycle associated with creating this meadow? You didn't really discuss that.

Mike Nadeau:

Great question. Yes, there is a mowing cycle. So, we use a nurse crop, which is something else we didn't touch on. A nurse crop is usually a fast-growing annual plant that will colonize the soil and add some shade to keep moisture in place, and also puts out some root system to hold the soil in place during rainstorms so you don't lose all your seed. That nurse crop will want to flower. All annuals want to do their thing in one year. So, we mow off the top of the nurse crop, all the flowers, because we want to prevent them from going to seed and having that nurse crop being there the second year. We just need it one year. So, an annual will die with the first frost and lay just like a mulch, and your little seedlings will love that. So, that's one mowing.

The other mowing is in the springtime just when dandelions are blooming. The Xerces Society says that when dandelions are blooming, that is when most of the hollow-stemmed, egg-laying insects have hatched and left your meadow. So, when dandelions are blooming is the time that we mow. And what I try to do is I try to mow less than half the meadow in one year. So, I leave some refugia, because you're going to kick out a lot of wildlife that's in that meadow that's being mowed. So, you want to leave some unmowed. And then, the following year, you mowed the part that you didn't mow.

And the reason why we mow is just to keep weed plants out, really. And we also use selective mowing to keep weeds down. So, if we have a problem, like on one meadow, red clover became a problem. And what we did was we scalp mowed the red clover with a weed whacker and reduced its figure, and then the wildflowers grew through it and overtook it. So, yes, very, very important. Mowing is a part of this. If we were in the right part of the country where we could burn, burning is good, but it favors grasses and doesn't favor wildflowers. So, thanks.

Audience:

What does it cost to convert, kind of per acre? Each acre.

Jeb Breece:

I'll talk to you afterwards. No, go ahead.

Mike Nadeau:

You're probably better with that than me.

Jeb Breece:

I do know the answer. I will say... I'll be... I think you read some things online about how this is a way to save money versus what you're doing conventionally. And that may be true over time. It is not true upfront, although it's not prohibitive either. Our yard is a little over three quarters of an acre, and we're not done, but it was about $15,000 to $20,000.

Mike Nadeau:

So, the key is, though, to think about it this way, and I'm not trying to sell this at all. The idea behind a wildflower meadow, if you took three quarters of an acre and landscaped it, you couldn't even think about coming close to landscaping that for $15,000. And what you get out of this kind of a landscape as time goes on is something way, way, way more productive than many landscapes. There are some beautiful landscapes that use natives, which great designers are here right now that have incredible colors.

But if you think about it, cost per square foot versus conventional landscaping, or I hate to use the word conventional, but even ecological landscaping, using shrubs and trees and perennials and things like that, if you tried to landscape three quarters of an acre for $15,000, you'll get laughed at. So, it's a bargain.

Jeb Breece:

Let's go somewhere in the back.

Audience:

Hi. With the mowing, are you also overseeding and reseeding every year and using that same tractor, or are you doing hand seeding with it?

Mike Nadeau:

So, repeating the question, with the mowing, are we reseeding, overseeding annually, filling in any gaps? So, we do overseed bare spots, thin spots, any place where there might have been erosion. So, come this spring, Matt and I will scan all of our meadows and see if there's any damage, and we'll reseed those spots. So, when we order seed for these meadows, we always over-order, and I store them. I store the extra seed so we always have it, because you oftentimes will not be able to get the same species again.

So, yes, that's important. We do not seed every year in order to get a thick meadow. You seed it once properly, and then you just repair with seed as necessary. Or, what's really cool, in the fall, cut your perennial flowers that are... cut your meadow plants that are full seed and shake them over the areas that are thin, or just lay them on the ground and let nature do the work.

Audience:

Right.

Mike Nadeau:

Yeah.

Audience:

Thank you. Could you speak to the impact of ticks in this-

Mike Nadeau:

Oh, this is a-

Jeb Breece:

Great question.

Mike Nadeau:

... great question. Yes, you're going to love this answer.

Audience:

I'm hoping.

Mike Nadeau:

So, I'm going to give you some homework. There's a PhD by the name of Kirby Stafford, Dr. Kirby Stafford. He's just retired from the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. With this huge grant that he was given from the federal government back in the '90s and the 2000s, all the way up to 2007 I believe, he used my former landscape company on a couple of properties to test different materials and to test where ticks are and where they're not.

And what he did was he devised this very, very simple experiment. He took a six-square-foot piece of white polypropylene cloth and shoved it inside his shirt and exercised around the property and pumped it full of the CO2, because ticks sense warm-blooded creatures from your CO2 exudation. They don't really see you. So, then he took a dowel rod, put it through the cloth, and dragged it in different areas for X amount of feet, measured feet, and counted the ticks that jumped onto this white fabric.

And what he found was that where there is a change in elevation of vegetation, right at that change edge is where most ticks were. Also, in stonewalls. So, if you have lawn going to Pachysandra, right where the lawn ends, the Pachysandra begins, that's where the ticks are. Guess why? They want the white-footed mouse. That's their number one host plant. And that's where the mouse doesn't run through the middle of the yard yard because they'll get picked off by something. So, they stay along the edges.

Here's the punchline. He tested meadows over and over again and found no ticks. None in the meadow. In the pathways along the edges, he found ticks. But in the meadow itself, there's no ticks. So, you can look up his work, Dr. Kirby Stafford. He wrote a huge beautiful manual. You can Google it right down to ticks and meadows, and the pages will come up. It's really beautiful. I love being able to say that. Someone in the back, right there.

Audience:

I think part of what you're saying is that the meadow is both visually appealing and also productive. So, you get to have the visually appealing part that you might have with the lawn, but it's also productive. And so, that's really great. But my question is, does it end up being at some point too much of a good thing, good defined the way you're defining it, in the sense that does anything regulate the growth of the meadow vertically, for example? Because if not, it might be really problematic.

Jeb Breece:

And be kind of out of control. Yeah, I'll take it first-

Audience:

And not pretty.

Jeb Breece:

... and then hand it off. For anybody who didn't hear the question, sounds all great, but what about over time? Can we have too much of a good thing here? Can we grow big, too flowerful, too beautiful? And I think there are a few answers here. One, Mike touched on with the mowing, which is designed to stop the natural progression in of the woody plant species that would eventually get bigger. But also, Mike's putting together a seed mix that's going to meet most of the objectives you're looking for, which you'll decide what those are. But also, you're putting these plants in their natural habitat. They're going to grow to their natural height, not more. So, the plant whose natural height is three feet is going to grow to three feet. It's going to stop there.

Mike Nadeau:

So, the best soil for a meadow is the [inaudible 00:52:54] soil, soil that's really poor. And if you choose your plants wisely, you can't be too, too picky because if you want a sustainable meadow, you need certain plants that fill certain niches. So, the reason why I like to use 40% grasses is because they're tough, they stand up, and they also have very finite heights. And they have beautiful flowers. Lots of people don't realize they're influorescences. Not true of the flowers. But they're really pretty.

And the winter meadow is, to me, especially if we get snow, not like this year, it's... think about it. It's like a kinetic sculpture. It constantly moves. It rustles. It's absolutely beautiful to walk through. But the concept of it being too much, what happens to a wildflower meadow over time, from what I've heard from most of my clients, is that they long for the early years, because that's when the really sexy flowers are out and they're in big profusion. And as the meadow matures, there's less sex appeal, if you will, but more resilience, more diversity, more variation in the vegetation.

So, it's a different kind of sexiness. I think that having grasses next to the asters, and the have asters have seneses?r the season, and they have those tawny seed heads against that bronzy foliage, that to me is flowers. So, you have to change... you don't have to, but I think anybody that goes for a wildflower meadow needs to change their idea or their mindset or their aesthetic of what is beautiful. What is beautiful is what attracts nature, what feeds nature. And we are nature. So, looking at a meadow that used to be a lawn that was a big time suck and a big energy input, and looking what it brings you.

I'll tell you one quick story. So, a client in Fairfield, Connecticut... I had these two girls that called me Mr. Meadowscaper. They never called me Mike. They called me Mr. Meadowscaper. They were the greatest two little kids. Husband was a golfer, did not want any meadow on the property. The wife wanted to reduce the lawn, and she loved the meadow idea. So, I said, "Okay, give me a quarter acre, I'll do a quarter acre, and then we're going to do a test with your kids." So, the wife went to the husband and they arm wrestled. She won.

We did the little meadow, and then I mowed a path through it, and I mowed a little circle at the end and I put a table and chair in there, two chairs and a table. And I gave them each pieces of paper and I said, "I want you for five minutes to write everything you see, smell, feel, touch." And then I did the same thing out in the middle of their lawn. And they gave it to their dad, and their dad said, "Okay." So, that's the aesthetic change.

Jeb Breece:

Let's do maybe two more questions because Mike is staying after. We've got a reception afterwards. Plenty of time to do Q&A. So, we'll do one from this side and one from that side.

Audience:

So, it seems like you really need an expert to help in the beginning stages of this. Ultimately, say you're five years in, can the committed layperson maintain this with the mowing in the spring, or do you need to be in partnership with someone like you for as long as are on this property?

Mike Nadeau:

So, that's a great question, and I know that's cliche, but that is a great question. The committed layperson is the key. So, if you are involved in watching the meadow evolve and watching the people maintaining it, absolutely after three to five years, you should be able... depending on the size too, if it's a quarter of an acre or half an acre, one person could definitely deal with that.

Yes. So, the answer is yes, you can take care of it. But all of those things have to be done right from the get-go. So, the site preparation has to be perfect, or as close to perfect as you can get it. The seed mix has to be right. The sowing has to be right. And then the maintenance afterward. By the way, watering, we don't water our meadows. The seeds will wait. One thing you definitely don't want to do is water, because if you stop, guess what? You've got spoiled rotten plants, and they will grow. So, good question.

Jeb Breece:

A tough act to follow over here.

Audience:

Are there any... Oh, no, you go.

No, you go.

Okay.

Jeb Breece:

Go at the same time. You can both go.

Audience:

Are there any times when you'll use plugs instead of seeds?

Mike Nadeau:

So, the question is, is there any time I'll use plugs versus seed. Generally, if you want to take $5 bills, put them green side up and pin them on the ground, that's about what it's going to cost you to do plugs in a good-sized manner. It's instant gratification, which I love. It's wonderful. I use plugs quite a bit. I usually use them in the second year, and I usually use it to stylize my meadows.

So, if you want, say, red lobelia, and you want swaths of them, you plug it, in the second year. You don't want to do it in the first year because you are mowing the nurse crop and you're going to be mowing your plug plants, and you won't get any flowers, and you'll be weakening them. So, I usually infuse the plugs in the second year. Good question.

Next question.

Jeb Breece:

We'll do one more since you two shared so nicely.

Audience:

So, if instead of starting with a grass that you're converting and that has soil, you were to start with a large area of gravel, what would you do?

Mike Nadeau:

Gravel's a great substrate to grow meadow in. All you need is a little bit of organic matter, percent, percent and a half organic matter. So, I would mix sub-soil with a little bit of compost, mix that into the gravel, and grow your wildflower meadow seed right through that. That would be a very different species choice, though. You'd want something that would be drought tolerant. Most gravel is very alkaline, so higher pH. You might want to test the gravel. Because if you have granite gravel, that could be very low pH.

Audience:

Thank you.

Jeb Breece:

So, perfect. Thank you, Mike. And before I let everybody go, two quick things. One, all of these talks are in partnership to benefit a local not-for-profit. In this case, Salisbury Association Land Trust, who Mike and I have both worked with on putting together a meadow, so you can all track its progress as you traverse Main Street. And the sidewalk that the town built goes straight there. So, you can get your coffee at the White Hart and walk on down.

The second is that we have three more great talks coming up. Page , who's right here, with Deb Munson, Toshi, and then onsite at Great Mountain Forest with Star Childs

Mike Nadeau:

Deb Munson. And Page. Rock stars. Those are the rock stars.

Jeb Breece:

This filled up, so don't wait till the last minute. Sign up, buy your tickets now. And we hope that you enjoyed this, and we hope that we'll see you at those.

Mike Nadeau:

Thank you, everybody.